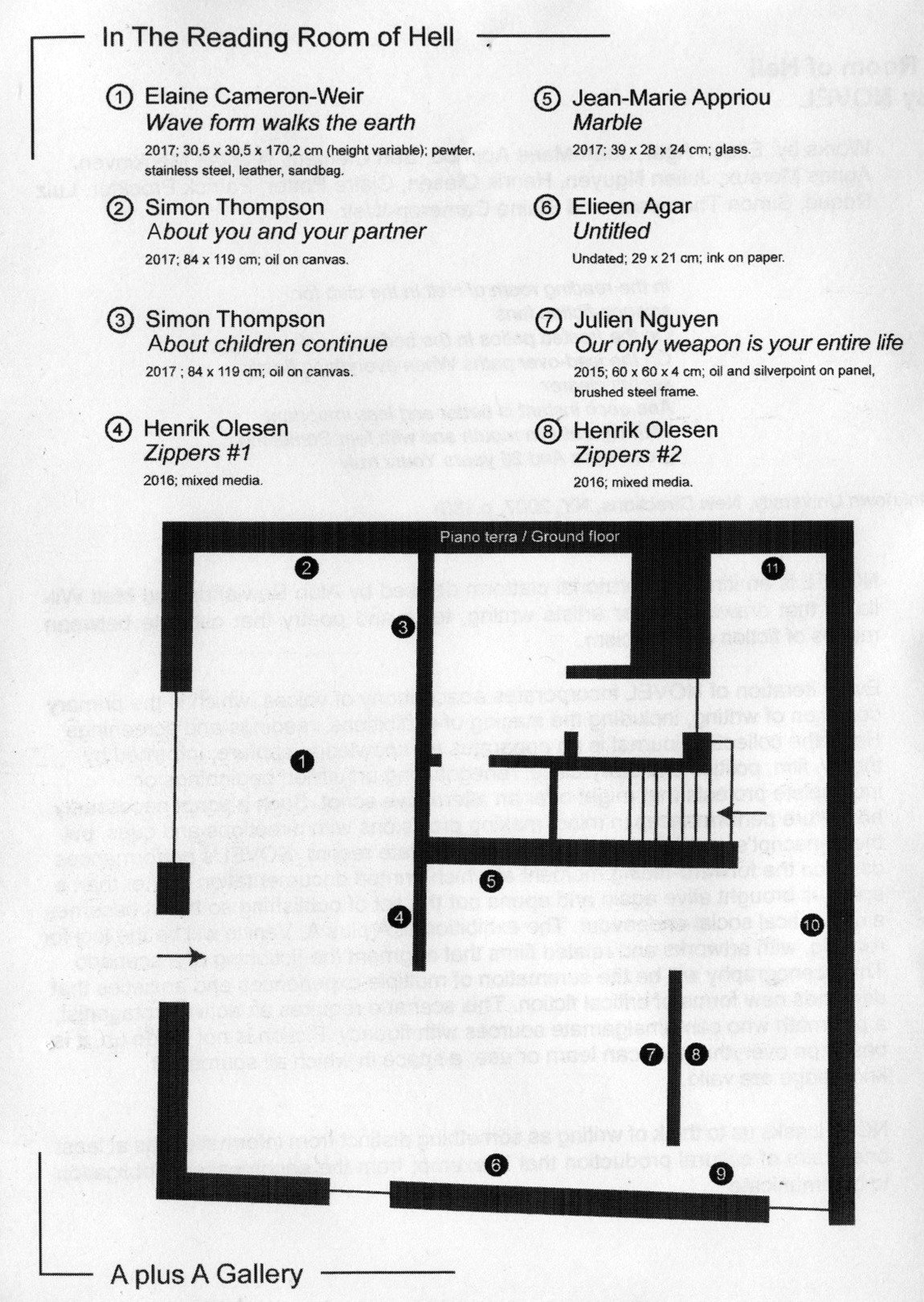

In the Reading Room of Hell

In the Reading Room of Hell

curated by Alun Rowlands & Matthew Williams

A plus A Gallery

Calle Malipiero 3073, San Marco Venezia

aplusa.it

24 February - 12 May 2018

Preview: 24.2.2018 h 18

Con una performance di Claire Potter

“In The Reading Room of Hell” at A plus A Gallery, Venice - Mousse Magazine

“In the Reading Room of Hell” at AplusA - ArtForum

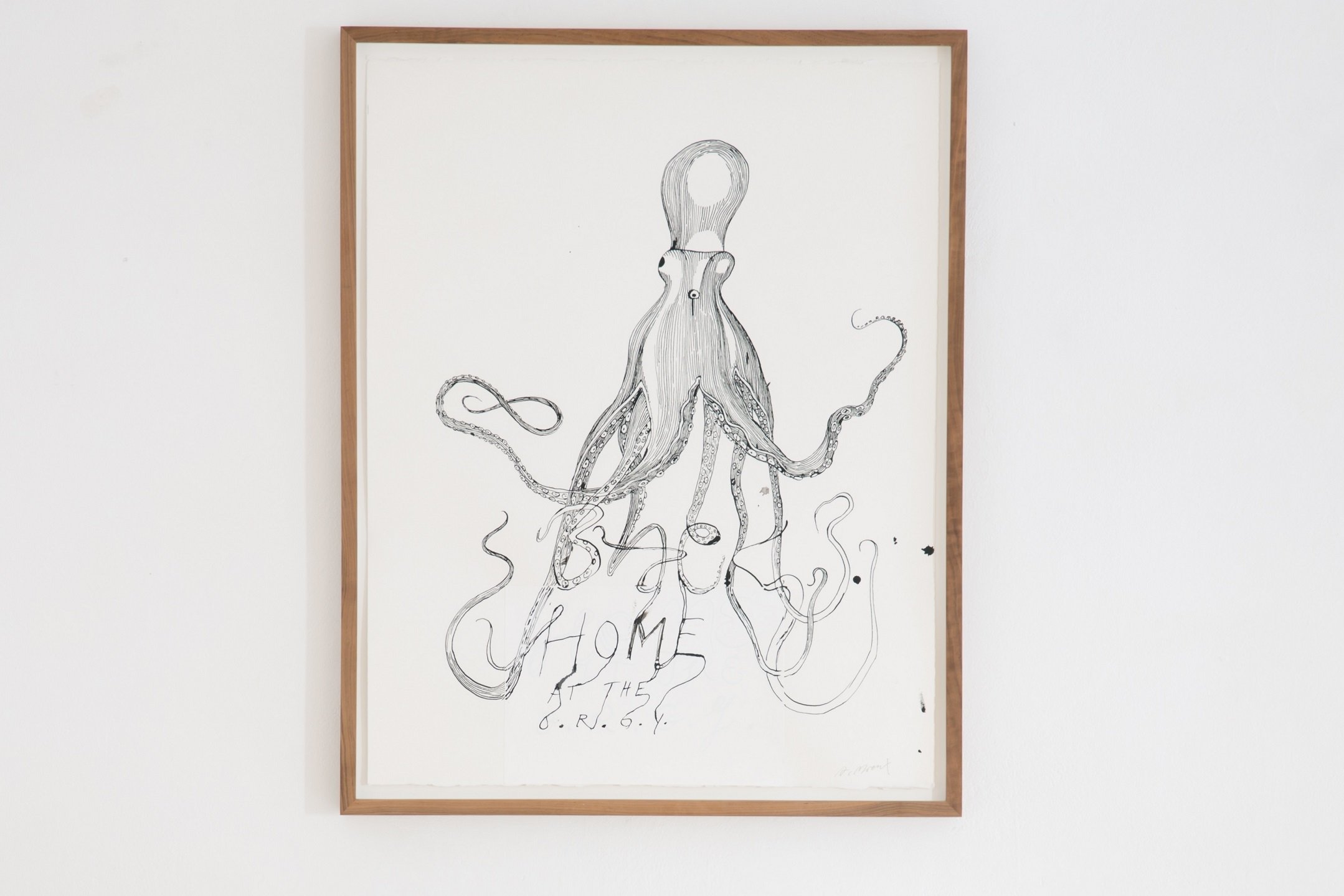

Jean-Marie Appriou, Marble, 2017, 39 x 28 x 24 cm, glass

Nella sala di lettura dell'inferno

Nella sala di lettura dell'inferno Nel club degli

amanti della fantascienza

Nei cortili coperti di brina Nei dormitori di transito

Nelle strade di ghiaccio Quando ormai tutto

sembra più chiaro

E ogni istante è migliore e meno importante

Con una sigaretta in bocca e con la paura Talvolta

gli occhi verdi E 26 anni Un servitore

- Roberto Bolaño

Bolaño, Roberto. ‘In the reading room of hell’, The Unknown University, New

Directions, NY, 2007, p.135

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Wave form walks the earth, 2017, 20.5 x 30.5 x 170 cm (height variable), pewter, stainless steel, leather, sandbag

Simon Thompson, About you and your partner, 2017, 84 x 119 cm, oil on canvas

Simon Thompson, About children continue, 2017, 84 x 119 cm, oil on canvas

Henrik Olesen, Zippers #1, 2016, mixed media

Jean-Marie Appriou, Marble, 2017, 39 x 28 x 24 cm, glass

Eileen Agar, Untitled, undated, 29 x 21 cm, ink on paper

Julien Nguyen, Our only weapon is your entire life, 2015, 60 x 60 x 4 com, oil and silverpoint on panel, brushed steel frame

Henrik Olesen, Zippers #2, 2016, mixed media

Agnes Moraux, S.B. 2017, 37.5 x 27.5 x 2.5 cm, ink and coloured ink on paper

Ben Clement, Spermatorrhoea (baby leg #3), 2017, 30 x 22 cm, cast high density polyethylene and steel mount

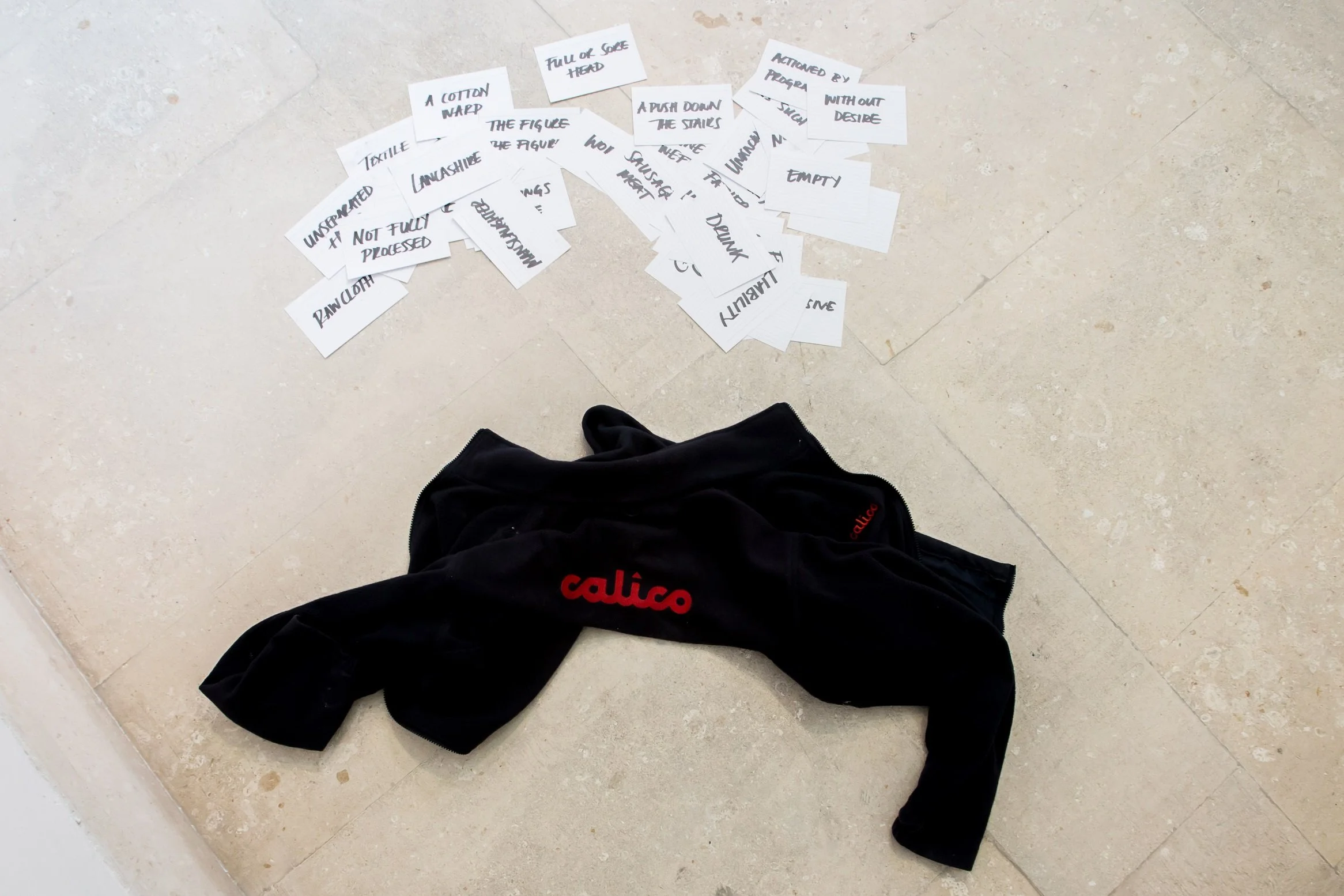

Agnes Moraux, Back home at the O.R.G.Y. 2017, 66.5 x 52 cm, indian ink on paper

Patrick Proctor, Figure Studies, 1963, 56 x 38 cm, pastel on paper

Ben Clement, Wilhelm kannegiesser die grossen erfolge der schropftherapie, 2017

Luiz Roque, Modern, 2014, 4’. 16 mm transferred to video

Henrik Olesen, Zippers #3, 2016, mixed media

Patrick Proctor, Composition with two figures, 1965, 28 x 21 cm, mixed media on paper

Alastair Mackinven, Untitled, 2017, 30 x 40 cm, watercolour and pencil crayon on paper

Eileen Agar, The witch, 1974, 18 x 39 cm, collage on paper

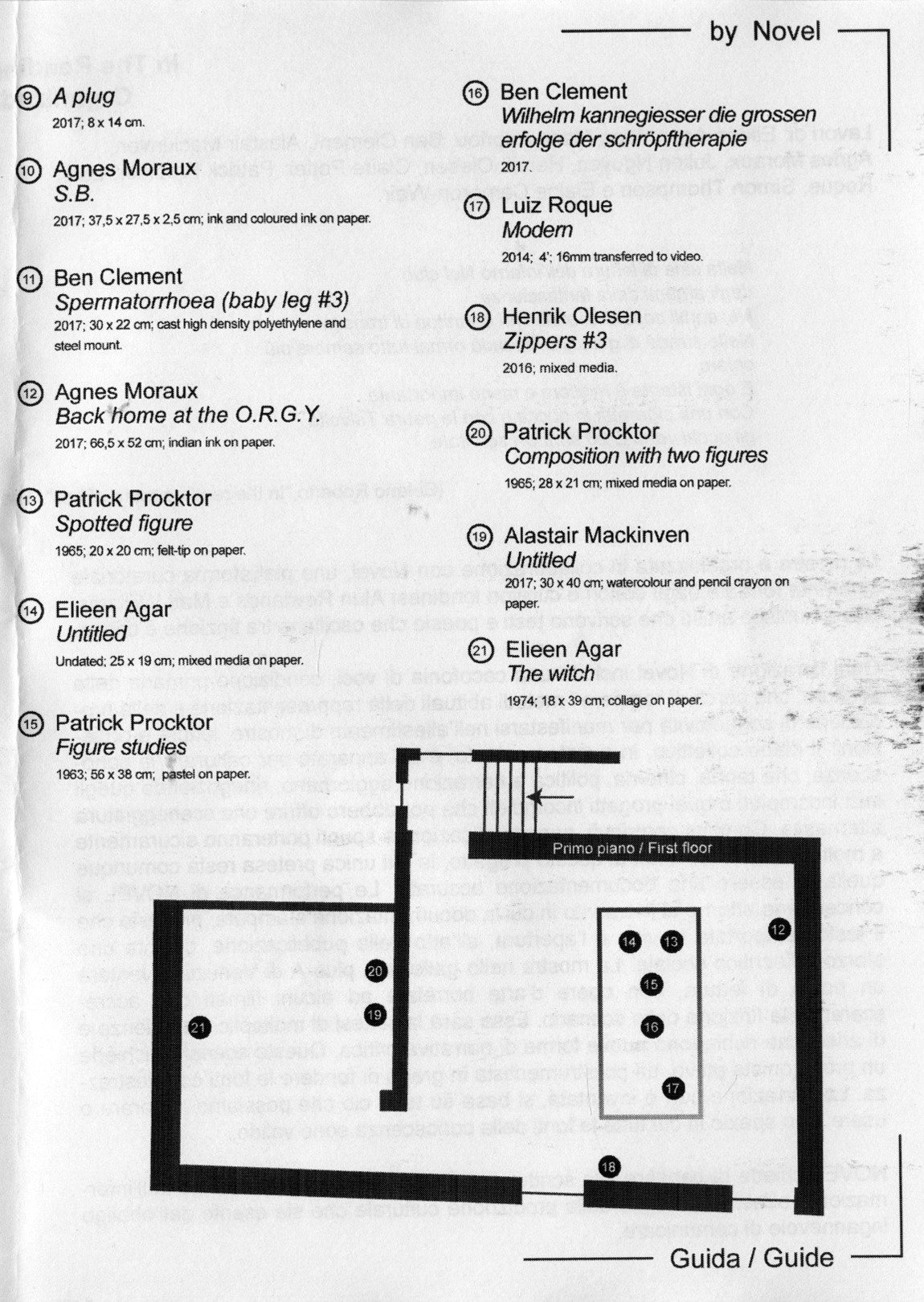

Claire Potter, Calico, 2018 (spoken word performance)

Ben Clement, Spermatorrhoea (baby leg #3), 2017, 30 x 22 cm, cast high density polyethylene and steel mount

We would like to thank all the artists for their participation and the following for their kind support: Aurora Fonda and Sandro Pignotti; Cabinet Gallery, The Redfearn Gallery, (both London); Jan Kaps, Cologne; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo; Reena Spaulings, New York; SCHLOSS, Oslo; Neue Alte Bruecke, Frankfurt; Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles; dépendance, Brussels

NOVEL is an editorial and curatorial project, publishing artists writing and texts that oscillates between modes of fiction and poetry. NOVEL acts in-between the potential performance of a script, and the indeterminate transcript of the event. The journal hosts a cacophony of voices that coalesce around writing as a core material of a number of artists exploring language and the speculative force of fiction. Here, art writing is an apparatus for knowledge capture, writing as parallel practice, writing as political fiction, writing as another adventure, renegotiating unfulfilled beginnings or incomplete projects.

La mostra è organizzata in collaborazione con Novel, una piattaforma curatoriale itinerante fondata dagli editori e curatori londinesi Alun Rowlands e Matt Williams. Novel riunisce artisti che scrivono testi e poesie che oscillano tra finzione e critica.

Ogni iterazione di Novel include una cacofonia di voci, condizione primaria della scrittura, che cerca di rompere i metodi abituali della rappresentazione e della produzione di soggettività per manifestarsi nell’allestimento di mostre, letture e proiezioni.

Il diario collettivo, in questo contesto, è un apparato per catturare la conoscenza, che teoria, cinema, politica e narrazione aggiornano, rinegoziando quegli inizi incompiuti o quei progetti incompleti che potrebbero offrire una sceneggiatura alternativa. Continui contributi, nuove indicazioni e spunti porteranno sicuramente a molteplici sviluppi futuri di questo progetto, la cui unica pretesa resta comunque quella di essere una documentazione accurata.

Le performance di Novel si concentrano attorno al momento in cui la documentazione stampata, piuttosto che il testo, è riportata in vita, e l’apertura, all’atto della pubblicazione, diventa uno sforzo autocritico sociale.

La mostra nella galleria A plus A di Venezia diventerà un posto di lettura, con opere d'arte correlate ad alcuni filmati che accresceranno la finzione dello scenario. Essa sarà la sintesi di molteplici esperienze e di ansie che richiedono nuove forme di narrativa critica.

Questo scenario richiede un protagonista attivo, un polistrumentista in grado di fondere le fonti con destrezza. La narrazione non è inventata, si basa su tutto ciò che possiamo imparare o usare; uno spazio in cui tutte le fonti della conoscenza sono valide.

‘In the Reading Room of Hell’, considers the lure of storytelling within contemporary art. The exhibition’s title is drawn from a poem by Roberto Bolaño. The poem’s sequence of spliced prepositional phrases and transitive nouns were utilised in the curatorial organisation of the exhibition. Questioning why we tell stories about and through art, and for whom? What do these stories signal? What do these stories convey as evidence? Who has the right to tell them and when? How does this change when the stories of art are written as fiction versus non-fiction, experimental text versus essay, the work of community advocacy or political activism versus the practice of objective reportage? When is the original image, action, or object of study overwhelmed by too much storytelling? Why do we tell stories about and through art, and for whom? What is the relationship between the stories we tell and the realities of history, power, and systemic violence? Is there an efficacy of confessional, and emotional modes of storytelling, as they appear alongside their analytical, philosophical, and political others? This exhibition project orchestrated different artistic processes to form a narrative short circuit that would exceed the context of the gallery. Language, beyond communicative function, operated as a plot and the exhibition an occasion for circulating subjects among objects in ways that elicit more than looking and reading. Works from specific international artists forged four chapters including a presentation of historical works from the archives of Agar and Proctor. Each chapter contained a body of work with the site of the gallery becoming a locus for reading across alternating subject positions and their narration.

Attracted by the power of image, in particular, sensations that stem from vision, Luiz Roque’s work traverses the genre of science fiction, the legacy of Modernism, pop culture and queer bio-politics, in order to propose and understand visually sensual narratives. Modern (2014) departs from an exploration of Henry Moore’s Recumbant Figure (1938) in dialogue with the fashion appeal of the performance artist Leigh Bowery; a key figure in the London club culture between the 1980s and 1990s. The film considers binary notions of stillness and dance, history and future, reflecting on Roque’s interest in the relationships between body, choreography and gender with the legacy of modern sculpture.

Claire Potter, Calico, 2018 (spoken word performance)

Simon Thompson, About you and your partner, 2017, 84 x 119 cm, oil on canvas

Originally trained in law and history at Université Libre de Bruxelles, Agnes Moraux has in recent years developed a prolific drawing practice of which nothing has been exhibited, her imagery referencing both comics/pulp culture (Frank Frazetta) and the old masters (Dürer, Titian, Pisanello). Moraux has included and excluded drawings of masks, 19th century cloaks, fights, daddydom, seascapes, Neanderthals and a selection of birds, mostly waders or fowl.

Agnes Moraux

Back home at the O.R.G.Y, 2017

Indian ink on paper, 66.5 x 52 cm

courtesy SCHLOSS, Oslo

Eileen Agar, The witch, 1974, 18 x 39 cm, collage on paper

Julien Nguyen, Our only weapon is your entire life, 2015, 60 x 60 x 4 com, oil and silverpoint on panel, brushed steel frame

“What about bodies that don’t matter? Or, bodies that do matter as a means but not ‘as an end’, that is, as a Subject. These are bodies that don’t own themselves, aren’t allowed to name themselves, regulated objects who are assigned their being only through that being’s violent effacement, through its denial.Can these bodies that don’t matter even be represented, self-represented, at least? If so, could they, as a kind of nothing, as a negation, even matter to themselves or to each other as a group? If you had to choose but couldn’t choose both would you rather have a body or be a self? The former might ask: how do I make myself a body, whilst the latter would say: how do I become a self? These questions assume a sense of agency or autonomy to do and to be, to have a kind of voluntaristic entry into systems of (re)production. But what kind of non-matter is a negative body anyway?; Is it more than derelict viscera? Unemployed negativity? Or vacant possession? We can talk about fixed bodies (like fixed capital or machines) and possible bodies (like variable capital or workers’ bodies), and we can talk about subjectified bodies, racialized, gendered, and queer bodies, or national bodies, bodies-without-organs, paranoid bodies, drugged bodies, family bodies, disorganised bodies, computer bodies (Turing’s hetero/homo binary machines), servant bodies and post-human bodies. How to deal with them? A machinic body could be thought of as the consequence of a tool body, largely superseding it, wherein a body’s relation to the object is based upon technique or artisanship directed toward a single aim and singular, as opposed to a machinic body that could be thought of as compartmentalised yet systematic, part of a greater unity (a factory): this division would be called something like formal and real subsumption, respectively, of bodies under the processes of capital, its imposition of the wage relation to produce surplus value in order to accumulate more of itself through the market, to persist as a mode of production, a totality of social relations. Or enslavement and subjection, respectively, now in one body. But do machinic bodies always produce value? What about unproductive bodies or surplus bodies that can’t reproduce themselves at all?”

Luiz Roque, Modern, 2014

Eileen Agar, Untitled, undated, 29 x 21 cm, ink on paper

Alastair Mackinven, Untitled, 2017, 30 x 40 cm, watercolour and pencil crayon on paper

“As if in a garden of delight, a field, or an opium den, the actors are lying, crouching, whirling, reassembled on walls and floors. A still life replete with inanimate matter manifesting length, breadth and depth. The scene isn’t entirely linear. It’s closer to a system of exchange. We built them, but we do not understand them. We are familiar with their essential attributes, but because they are composites they are paradoxical.

The idea of phenomena is implicit to the diachronic. Stepping out of the two dimensional barrier, ideas, transformations, and states of being exhibit semi-fantastic portrayals of respiration and hysterical fever. The act of becoming and energy production is crucially, and fundamentally, at work here. Milk in its jug. A germinating crop, yoga at its gate/bridge/arch. Crayon graffittied rainbow sirens exude a kind of ambiguity, or indifference. Stuck in time and movement, they are adorned by aluminium cast crickets, fragile lilies, and glass fly pneus feeding off of marbled plastified heads.”

- Jennifer Teets, 2017

“The Lotus Eater was not asleep, like you might have expected. Few Lotus Eaters sleep and fewer dream in fact. The Lotus Eater did dream however, even when he was not asleep; he had dreamed of the coronation and of a movie poster with a black and white heart, bisected by an inverted black and white background, baring the tagline for a film un-saw : YOU ARE ALONE, YOUR ONLY WEAPON IS YOUR ENTIRE LIFE. Perhaps the film was based on a video-game because sometimes they are, now.

The Lotus Eater had a distorted perspective on things, but knew that in cases of adequate force, distortions could be imparted onto things, and would therefore, no longer be distortions. In other words, they were often images of things to come.

He had told the Dog this, and believed that he believed it, if only half- heartedly.

Let it be known that there was, without question, movement in the life lived by the Lotus Eater. It remained to be seen, however if this was the motion of a great ship to harbour, to bare out the multitudes on new worlds or that of the raft of stow-away, cast-away, and cast-o : drifting further from anchorage, but let it be said, at least to lands unlearnt. Again, motion may not generally be understood as the purview of big time couch potato types and desert island dwellers, but discard your prejudices, things often differ from the common view, even if most of the time, they don’t.”