Growing Up Absurd

Growing up Absurd

Problems of youth in the organised system

Herbert Read Gallery

Kent Institute of Art & Design

Canterbury, Kent

supported by the Arts Council of England

28 January - 26 February 2005

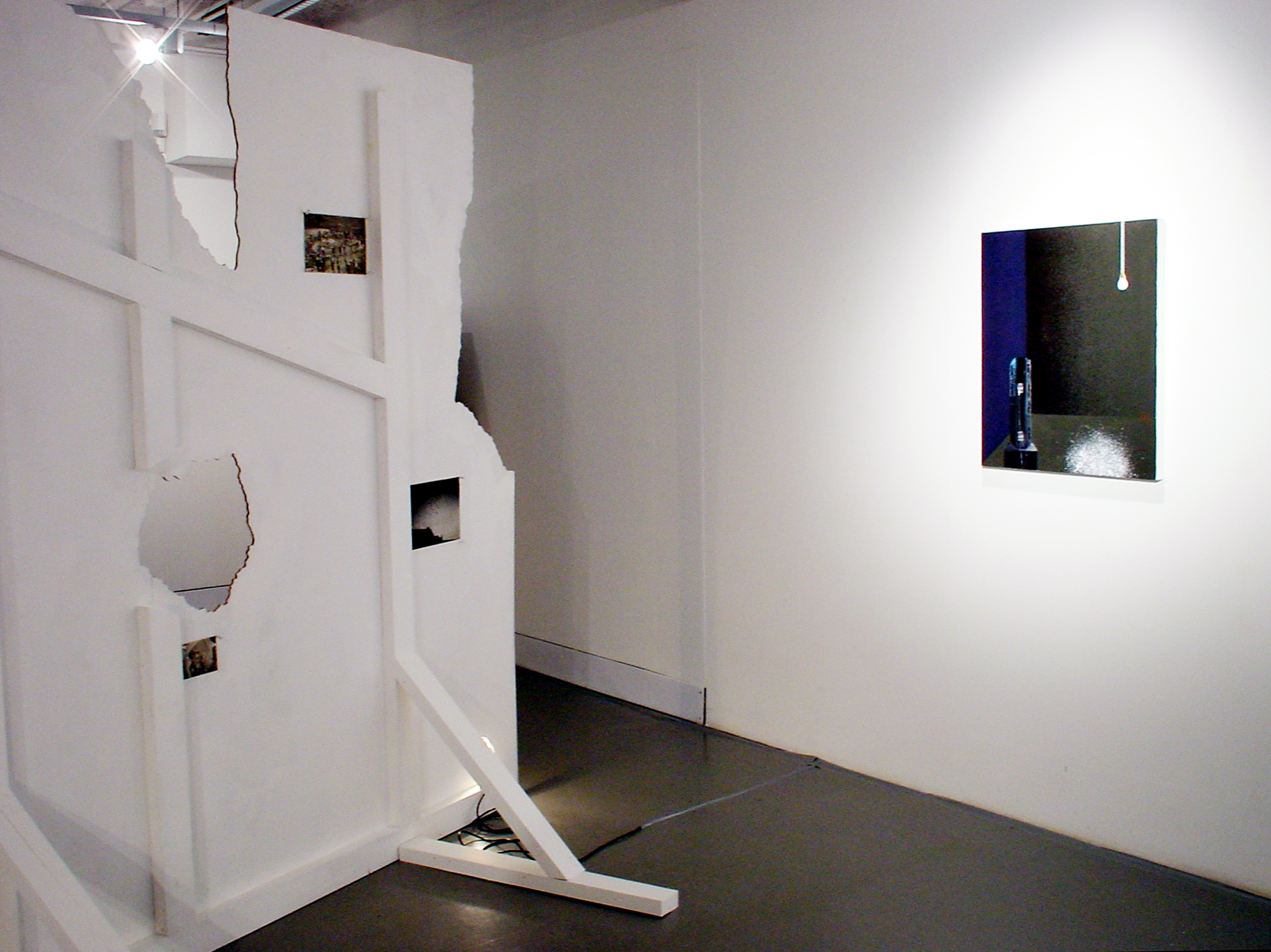

Dexter Dalwood, ‘Ian Curtis 18.5.80 (small)’, 2001oil, on canvas, 62.5 x 74cm

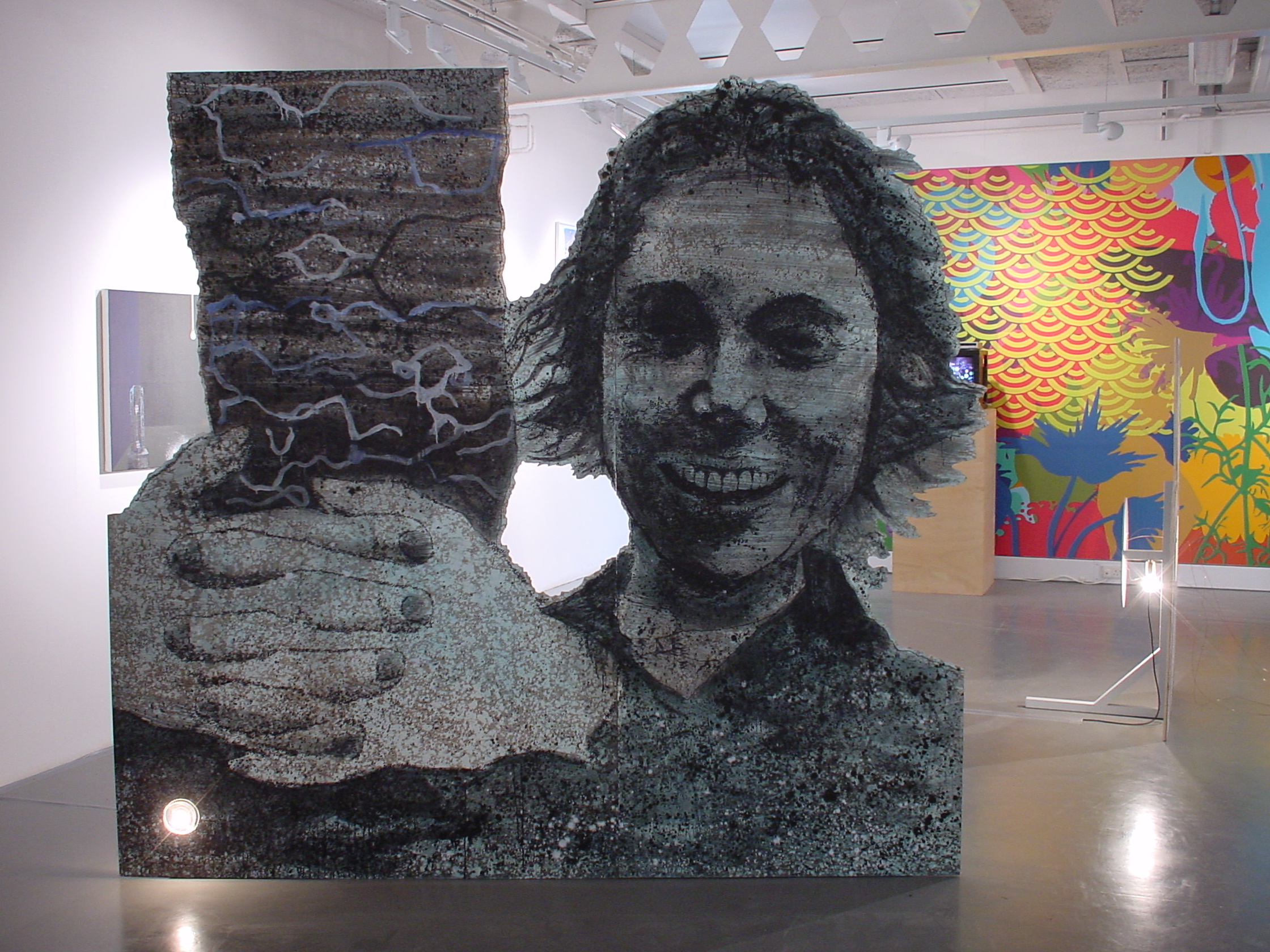

Mark Titchner

We are the solution

2006

Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System. (New York: Random House, 1960; London: Victor Gollancz, 1961)

Growing up absurd brings together artists from the UK, Europe and USA. The exhibition takes its title from Paul Goodman’s Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System. Goodman’s landmark study of the conditions of adolescence and early adulthood railed against the 1960’s establishment that he saw as destroying the dreams and lives of youth. The book puts forth the idea that western society is a paradise of consumerism, a "confused, seduced, spoiled mass society”, staggering from one problem to the next.

The exhibition will seek to explore the current status of culture through the filter of adolescence opening up an often extreme and varied terrain. Here, adolescence is not merely a passing phase, a hazing into adulthood, but a parallel fluid universe in a state of becoming. It marks a territory that is closely connected to the present while symbolically containing the seeds of the future.

Contemporary art has treated adolescence as an indispensable point of reference through radical gestures, violations and impatience. From the revolt of the historical avant-gardes, through the counterculture of the 1960s art has explored and exploited the eternal adolescent. The artists in Growing up absurd recognise youth as a mental state, an existential condition with an overwhelming impact on lifestyles and trends.

Their reflexive and diverse approaches embody a state and love of extremes. Adolescence represents an Arcadian field of introspection that is both agitated and curiously elusive. Moments of reverie and observation collude with redefinitions of deviant behaviour and the forging of subcultures. Adolescence represents an Arcadian field of introspection that is both agitated and curiously elusive. Moments of reverie and observation collude with redefinitions of deviant behaviour and the forging of subcultures. Adolescents are omnivorous, tireless consumers of culture. The market saturates society with the precious commodity that is youth. Youth is a vaunted condition, a place to aspire to in perpetuity. It forms part of the dream, a decisive segment in the strategy of consumption.

The exhibition will take the viewer on a cruise filled with visual seduction and polymorphous adventure. The curatorial impetus will be to realise scenarios that will function like unstructured chapters in a never to be finished novel. The artists’ work will conspire to outline an alternative present prompting us to imagine ourselves somewhere else through a hybrid bricolage of confrontation and significance. The exhibition will portray a restless disaffected territory of creative energy through a sea of potential and possibilities. Its ambition will be to form new constellations of thinking and engagement with our complex contemporary culture.

Growing up absurd

by Mark Beasley

First published in Frieze Issue 91 , May 2005

A copy of Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd (1956) was recorded among the items found in Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski's cabin hidden high in the Montana woods. Goodman, acknowledged as one of the most influential social critics of the 1960s, was adopted as ideological stepfather by the counter-cultural youth movement and made constant campus appearances. Kaczynski, a former mathematics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, rejected academia, preferring to attack it – technological progress he deemed disastrous for mankind – and was christened ‘the Unabomber' as a result.

Goodman's landmark study of youth in American society served as the title and backdrop for an exhibition that sought to examine present culture through the ‘filter of adolescence'. Curated by Alun Rowland and Matt Williams (and subtitled ‘Problems of Youth in the Organised System') the show drew on artists from the UK, Europe and USA and examined the ‘parallel fluid universe' of the teenager – a demographic that sprang from the ‘Rock around the Clock' generation of the 1950s – the ideological and consumptive advent of youth – and that has either been ‘sold to' or, in the words of Goodman disciple and leader of the Yippies Abbie Hoffman, ‘sold out' ever since.

Olaf Breuning's staged photograph We Only Move Wehen Something Changes!!! (2003) is suggestive of 18th-century history painting. As Sir Joshua Reynolds said of his craft, a history painter, whether he depicts kings or beggars, ‘paints man in general'. Man, or in this case youth, is depicted as a cluster of clown-nosed, bewigged pirates slumped against an immovable concrete structure daubed with a slogan that constitutes the title of the work: an image of lumpen youth resigned to its fate and the occasional mis-spelling.

Jochen Klein

Untitled | 1997

Oil on canvas

102 x 147 cm

Pinakothek der Moderne, München

Breuning provides what is arguably the centrepiece of the exhibition, the dual video projection Home (2003), in which one of the protagonists – ‘I'm not an intellectual but a little brain work never hurt anyone' – all junkie thin, straggly hair and pale glowing eyes, tells tales of his friends' antics. The work comprises a series of filmic vignettes in which the affirmative ‘I EXIST' has been vomited on snowy ground, smiley pill-swallowing French students are carried off by winged ghosts, and hapless Death Metal teens cover each other in shaving foam and cheap lager. Meanwhile comic-book Hip-Hop gangsters head to an Amish village, where they strip a villager and chase their E.T.-masked victim through fields of cornrows. All are seen as passive consumers, spinning the spoon-fed fiction of pop, rock and film to bewildering consequence. But there are echoes too of Mike Kelley's cover notes for Dan Graham's Wild in The Streets (1994), in which he bemoans a generation seduced by the cult of youth ‘blind to the fact that our beliefs were a by-product of the capitalist commodity fetishism and planned obsolescence we were supposedly against'. On Breuning's part there appears some frustration at the profligate sensibilities of the day.

A psychedelically charged frieze by one-person collective assume vivid astro focus depicts exotic birds, a Janis Joplin-style carnival singer and fluorescent geometrics – a feast of camp excess so achingly hip it hurts. Close by, in Cory Arcangel's video Cat Rave (2004), a cat sits surrounded by spinning disco lights. The extremes of youth are recalled in Kaye Donachie's drawings of scantily clad female Manson family members: the ‘flirty fishing' of Manson's ‘murd-molls' drawing naive youth to the flame. Jochen Klein's wistful adolescent figures caught in naked Arcadian repose accept the avaricious gaze of the consumer. Meanwhile in Dan Attoe's painting Atonement (2004) a mini-dystopia of islands rises from the ocean, providing scant shelter for their inhabitants, who act out personal fantasies as romanticized isolation turns sour.

Charles Atlas' film Hail the New Puritans (1987), a simulated day-in-the-life ‘docu-fantasy' starring Michael Clarke, explores the metropolitan night and day of 1980s London. As the camera follows Clarke, we are privy to yesterday's dole-dandyism, constituencies seemingly formed through shared aims both ideologically and stylistically. Leigh Bowery, Trojan and Mark E. Smith all figure in a film that powerfully suggests a different kind of mark-making; a resistance through performance and provocative posing. In the far corner of the room Andrew Mania's drawings of beautiful boys explode in a dizzying money shot of scribbled patterns: youth as sullen commodity lifted from the pages of a Dennis Cooper novel.

How old are we? When was ‘youth'? In the main these are works about youth rather than by youth. Perhaps we consider it more at the point of irrevocable return, as the pathways back are lost in encroaching middle age. A tragic melodrama casts its shadow on Dexter Dalwood's painting Ian Curtis, 18.5.80 (2001). A solitary speaker cabinet and dangling light bulb occupy the corner of a spartan room in a beguiling memorial to the Rimbaud of a generation.

Goodman eventually disavowed the student revolutionaries who adopted his text – Hoffman among them – describing them as a mob of ‘witless narcissists' and bemoaning the metastising ‘ahistoricity' of the young. ‘Growing up' is depicted as a world of lurching extremes, of Oedipal relations, challenging parental cultures but occasionally stifled by their presence. From what at first glance appears like the celebratory representation of a Dada-acid-flower campus revolution we are invited to tease apart the threads of adolescent activity to examine the delinquent silhouette in all its awkward, dumbstruck fragility and splendour.

Mark Beasley

assume vivid astro focus//

Cory Arcangel//

Dan Attoe//

Charles Atlas//

Olaf Breuning//

Dexter Dalwood//

Kaye Donachie//

Lothar Hempel//

Jochen Klein//

Andrew Mania//

Wolfgang Tillmans//

Mark Titchner//

Vey Duke & Battersby//

curated by Alun Rowlands & Matthew Williams

Olaf Breuning, 'We only move wehen something changes', 2002, C-print on aluminium, laminated, 122 x 155 cm

'One thousand years later'

Lothar Hempel

Every day a new pair of shoes. It has become a kind of ritual.

This morning Lilly picks up a pair of silver-grey Nike sneakers with light diodes in the heels that light up every footstep. Then she begins her patient daily trek through the streets, walking as if in a dream over stairways inside houses, through dormer windows onto roofs, and over scaffolding back to the sidewalk, descending manholes into the sewers, walking through subway tunnels, climbing up ladders and yet always ending up, hardly by chance, at the same places where she has started.

But now these places give a new and quite different impression, maybe because time has passed or because they have taken a new meaning in Lilly's inner map of the town.

The courageous edge of town. The shy harbour basin. The snotty shop window. She hasn't met anybody or spoken with anyone for months, but she doesn't miss it, because she is much too busy. She observes everything

painstakingly and memorizes every change meticulously. The continuing decay of the town indicates simultaneously the birth of something new, something wonderfully new, as yet without a name.

A certain blue in the a poster, fading in the sunlight into grey. A certain kind of resistant weed originating from the park and expanding into the neighbouring streets. A mannequin who's false lashes fall to the ground. The dust covering one side of the street in a thicker layer than the other. The smell in a chapel slowly growing less noticeable with time, and finally disappearing altogether.

The revolving door of one of the big cinemas is open. The air inside is stale and acrid. She strolls slowly through the high entrance hall past the drinks machines and enters the theatre through the swinging doors. Her eyes slowly get use to the semi-darkness and she takes a seat in the first row.

‘I have always sat in the first row' she thinks and looks at the big, pale rectangle of the screen in front of her. It's quite silent here, pleasantly silent. The chair is soft and Lilly is very tired and it's so nice to cit here. Is it a dream?

Suddenly an image appears on the screen, washed out and dark like an old photograph. A movement, cut short and a bit too slow. The colours become more pronounced, they are bluish and seem to come from far away. A

figure moves towards camera.

‘But that's Sissy, my Sissy!' shouts Lilly excitedly and she is startled because she hasn't heard her own voice for so long. The figure comes closer and soon her face fills out the entire screen. Big freckles on the pale, almost transparent skin. Small wrinkles show on her grinning face. The unreal hair.

‘Hello, Lilly', says Sissy with a maniac laugh, swaying her hips while she hugs a tree.

‘Hello, Sissy! I'm so happy to see you!' Lilly shouts back to her, laughing (she has never been happier).

Sissy: ‘Shall we watch the films now?'

Lilly: ‘Yes, all of them, and again and again, as long as you stay here with me!'

Sissy: ‘We are sitting next to each other, very close and our elbows touch lightly on the arm of the chair.'

Lilly: ‘And we are laughing about the same scenes!' Sissy: ‘Of course!'