The Glass Bead Game

The Glass Bead Game

Vilma Gold Gallery, Berlin

Schlesischerstr. 26

10997 Berlin

www.vilmagold.com

25 March - 30 April 2006

Curated by Alun Rowlands &

Matt Williams

Dirk Stewen

Untitled, 2006

framed print, wooden rod, two panels of ink on paper, confetti and cotton

122 x 148 cm

William Daniels

Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint Bernard Pass, 2006

oil on board

31 x 25 cm

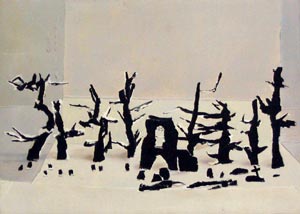

John Stezaker, Angel, 1988-1990

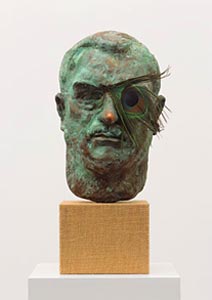

Steven Claydon, The Author of Mishap (Them), 2005

(Courtesy of Hotel, London)

Claydon’s The Author of Mishap (Them) is informed by J.G. Frazer’s ‘The Golden Bough’, an early 20th-century dissertation on magic and ritual that was widely denounced for its questionable methodology “a comparative anthropology by genre” rather than linear science. Mirroring Frazer’s logic, Claydon’s portrait is a composite of three heroic busts of political figures from this time, each embodying radically opposing beliefs. Substituting the traditional material of bronze for cast copper powder and resin, Claydon defiles his subject’s monumentality; the aged patina has been created through urinating on the object, both an act of defamation and a reference to Warhol’s egalitarian pop. Perched on a burlap-coated plinth reminiscent museum wall coverings, Claydon reinforces his sculpture’s historical stature while belying its association with the outdated. The peacock feather operates primarily as a formal device, adding a surreal and dilettantish air to the impoverished authoritarian relic.

Volker Eichelmann, Untitled129; Untitled 132; Untitled 141; Untitled 146, 2005, collage and watercolour on paper, 32 x 22.5cm each

(Courtesy of Andreas Huber Gallery, Vienna)

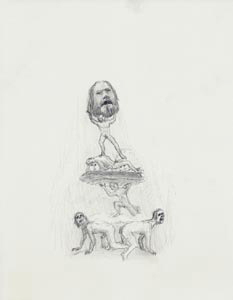

Jeff Davis, Le Fe' Pense, 2005, pencil on paper, 30 x 30 cm

Jeff Davis, Most Sovereign Sacrifice, 2005, pencil on paper, 11 x 8.5 in

Jeff Davis, Untitled, 2005, water colour, 11 x 8.5 in

Jeff Davis, Purple, 2005 pencil on paper, 30 x 30 cm

(Courtesy of Kerry Schuss, KS Art , New York)

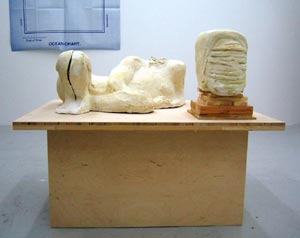

Thomas Houseago, Reclining Nude, 2006 Tuf-Cal, hemp, iron rebar, clay, 13 x 32 x 28 in (33 x 81.3 x 71.1 cm)

(Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery)

Sophie Macpherson, Great Boxes, 2005, wood construction, 140 x 70 x 70 cm

(Courtesy of Sorcha Dallas)

Adam McEwen, Ocean Chart, 2005,

180 x 120 cm

Seth Price, Painting Sites, 2000, video,

12 minutes, (Courtesy of EAI)

Stefan Rinck, Shelter Coat Madonna of the victim dog, 2006 sandstone carving,

100 cm x 40 cm

Florian Roithmayr, The centre is everywhere, 2005,

MDF Screen, 300 x 150 cm

Florian Roithmayr, Plan drawing (black), 2005, drawing on wood, 180 x 120 cm

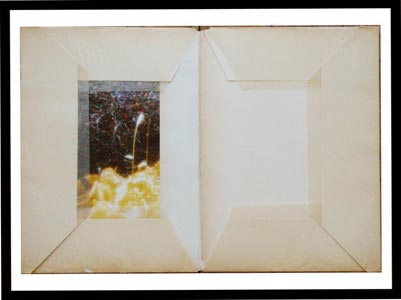

Dirk Stewen, Untitled, 2006, framed print, wooden rod, two panels of ink on paper, confetti and cotton, 122 x 148 cm

William Daniels, Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint Bernard Pass, 2006, oil on board, 31 x 25 cm

“I suddenly realised that in the language, or at any rate in the spirit of the Glass Bead Game, everything actually was all-meaningful, that every symbol and combination of symbols led not to single examples, experiments, and proofs, but into the centre, the mystery and innermost heart of the world – into knowledge.”

— Hermann Hesse, The Glass Bead Game

Taking its title from Hermann Hesse’s visionary novel, The Glass Bead Game brings together a constellation of works whose connections are provisional, and constantly reforming. Each artwork becomes a move within a grand and invisible game—a gesture of thought translated into matter. The gallery space weaves together interrelated fictions that forma a language of broken connections. As in Hesse’s imagined Castalia, meaning circulates ritually, through correspondences and echoes that bind the sacred and the secular, the archaic and the contemporary. Signposting the way are images and objects colluding to form an entropic trail that define a restless territory of creative knowledge.

In Hesse’s novel, the Game is an ecstatic synthesis —a vast spiritual calculus uniting mathematics, music, and metaphysics into a single field of contemplation. The game integrates all fields of human and cosmic knowledge – sacred geometry, alchemy, hieroglyphics, mythology, harmonics, arithmetic, astronomy and magic. It is both ascetic and playful, an art form practiced not for possession but for revelation. To play the Game is to trace invisible harmonies, to thread connections between the sciences and the soul, between pure form and lived experience. The Glass Bead Game is a mode of playing with the total contents and values of culture and knowledge.

The exhibition translates the metaphysical architecture of the novel into the present tense. Dirk Stewen’s fragile paper constructions and evaporating marks recall calligraphic origins —notations of intuition, equations of decay. William Daniels’ Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint Bernard (2006) folds art history into itself, as if the Game’s archive had turned reflective, looping past triumph into painterly disintegration. Juliette Blightman’s diaristic works move between document and reverie, turning the everyday into a sequence of symbolic gestures—personal moves within the grander composition of culture.

Adam McEwen, Ocean Chart, 2005, 180 x 120 cm

Adam McEwen’s Ocean Chart is a map of nowhere (after Lewis Carroll), a field of potential coordinates where navigation becomes speculation. Florian Roithmayr’s sculptures rehearse the Game’s principle of correspondence —matter learning from matter, form impressing upon form. John Stezaker’s spliced portraits fracture recognition, revealing mythic structures beneath cinematic skin. Thomas Houseago’s figural sculpture stand as beings in flux—figures of becoming caught between ruin and birth. Steven Claydon’s hybrid effigies evoke the convergence of history, technology, and ritual in strange new orders of knowledge.

The exhibition itself enacts a contemporary Bead Game played not with symbols of music or mathematics, but with the mutable materials of image and form. Each artwork contributes a fragment of a collective syntax —the residual language of a civilisation endlessly remixing itself. Delicate drawings, wax sculptures, botanical collage, esoteric busts, appropriated imagery and found material are manipulated with transformative effect in correspondence, an open grammar of entropy and renewal..

The Glass Bead Game, both novel and exhibition, imagines a discipline of attention—a way of thinking through pattern, resonance, and transformation. Here, the artworks are not endpoints but conduits, diagrams of consciousness, meditations on transmission. Their alignments shift like constellations, hinting at another order. What remains is not harmony but a shimmering field of possibility. Between order and flux, symbol and sensation, we glimpse the architectures of thought as they fracture, recombine, and renew. The Glass Bead Game becomes not only a metaphor for artmaking, but a vision of culture itself as a living, self-transforming game.

John Stezaker, Untitled, 1988-1990

Juliette Blightman//

Steven Claydon//

William Daniels//

Jeff Davis//

Volker Eichelmann//

Thomas Houseago//

Sophie Macpherson//

Adam McEwen//

Seth Price//

Stefan Rink//

Florain Roithmayr//

Dirk Stewen//

John Stezaker//

Steven Claydon, Mutt & Jeff, 2006

“Stony carpets. Rimmed and buttressed basins. Tears of terraces. Matted filaments and curds. Thick leathery sheets brilliantly coloured, the intensity of hue varying as colonies of wax and wane. Rotten eggs. The arrival of the blue greens. Stony cushions, teetering columns and spiky armour. A ring of teeth. An endless variety of shapes, rays of light, trumpet-shaped mouths and elongated bodies. Packets of chlorophyll. Thrashing tails and giants. A mass of flailing threads and bulging out fingers. Ornate vases and bottles. Concentric spheres fixed by needles. Gothic helmets, rococo belfries and spiked space capsules. A creeping speck of grey jelly. A hollow sphere. A tiny ball. Needles meshed together to form a scaffold. A flower basket. A million tiny splinters or an intricate and beautiful lattice. An unfortunate woman who was loved with the god of the sea and as a result had her hair changed by a jealous goddess into snakes. An enemy, solitary, glued to the rock. Very odd shapes. A buttercup. a rose. Ghostly waves of light, writhing arms, a skeleton of stone, deposits ooze.”

extract from Steven Claydon 'From Earth' 2005, video, 4 minsutes, 27 seconds

'Painting Sites demonstrates Price's interest in the Internet's role as a vast interactive archive that makes accessible otherwise disconnected groups of cultural material, from fine art to popular music. The ease with which material from the past can be recovered and re-contextualized at random epitomizes the condition of postmodernity, in which previously fixed cultural canons have become fragmented, fluid, interconnected, and relative.

Painting Sites articulates this relativity by creating an ironic, fractured narrative using two classic forms of high culture and popular entertainment: painting and the fairy tale. Reproductions of paintings from various periods in art history, drawn randomly from the Internet, appear one after the other on the screen, as Price narrates a story he wrote in the style of a German Romantic tale. He begins: 'In the Wild Woods, west of the Hartz Mountains, lived a man named Ludwig Tieck.' Casting Tieck as the fictional protagonist signals the elliptical structure of the piece: he was one of the canonical Northern European fable writers. As the story unfolds, characters and locations change, and the tale evolves into an elaborate, improbable narrative, a labyrinth in which stories within stories double back on themselves in an endless deferral of resolution. Price manipulates the 'ideal' of narrative, with its perpetual promise of something meaningful to come.

Iconic images from art history appear, punctuating every phrase: Botticelli's Venus, Leonardo da Vinci's Pieta, and a brooding landscape by Jacob Ruysdael. For brief moments, our desire to correlate the images with the story creates an implausible synchronicity, and a pattern seems to emerge. The epiphany is quickly erased, as the erratic randomness of the image reasserts itself. The disjunction of logic in 'Painting' Sites evokes both the creative potential within the inherent randomness of the Internet and the dreamlike boundlessness of fairy tales, in which the ordinary world is disrupted in order to open up another kind of space, where the unconscious can explore the outer edges of reality."

Text and reading by Seth Price.

Music: "Two Portraits: One Ideal; One Grotesque," by Béla Bartók.

Thomas Houseago, Reclining Nude, 2006 Tuf-Cal, hemp, iron rebar, clay, 13 x 32 x 28 in (33 x 81.3 x 71.1 cm)